Overview

The fourth-century Arian Controversy was the most important Controversy in the history of the church and resulted in the acceptance of the Trinity doctrine. However, research and discoveries during the 20th century have shown that the traditional account of that Controversy is a complete travesty. Contrary to the traditional account:

Arius did not cause the Controversy. He did not develop a new heresy. He was a conservative. He attempted to continue the traditional teaching of the Alexandrian Church.

It was not a new controversy but continued the third-century controversy.

What was new is that, after the emperors legalized Christianity, the emperors decided which factions of Christianity to allow. In other words, the emperors were the final judges in doctrinal disputes.

The core issue in the dispute was not whether the Son is subordinate to the Father. All, including the Nicenes, accepted that the Son is subordinate to the Father.

The core issue was also not whether the Son is a created being. All, including the Arians, accepted that the Son is divine.

The core issue was whether the Son is a distinct Being. While the Nicenes claimed that the Son is part of the Father, the Arians maintained that He is a distinct Being with a distinct mind..

Arius’ opponents, Alexander and Athanasius, were not orthodox. They believed that the Son was part of the Father, namely the Father’s Word or Wisdom. This was similar to what the Sabellians taught, which was already rejected as heresy in the preceding century.

The anti-Nicenes did not follow Arius. Athanasius coined the term ‘Arian’ to falsely label his opponents with a theology that was already rejected by the church. But the term ‘Arian’ was and is a serious misnomer.

Nicene theology was not the orthodox teaching of the church. Arianism was the dominant view during the first five centuries.

The Nicene Council was not ecumenical. Emperor Constantine called it to force the church to a consensus. He used his position to ensure that the council formulated a creed according to his will.

Since research over the last 100 years has shown that the traditional account of the Origin of the Trinity doctrine is a complete travesty, this article is based on the writings of world-class scholars of the past 50 years, reflecting the revised account.

Arian Controversy

The ‘Arian’ Controversy of the fourth century was the greatest church controversy of all time.

The controversy began in the year 318 when “Arius, a presbyter in charge of the church and district of Baucalis in Alexandria, publicly criticized the Christological doctrine of his bishop, Alexander of Alexandria” (Hanson, p. 3).

Seven years later, in 325, after the controversy had spread from Alexandria into almost all the African regions, Emperor Constantine called a church council in Nicaea, where Arius’ theology was rejected and the famous Nicene Creed formulated.

However, in the decade after Nicaea, the church deposed all leading Nicenes and allowed all deposed Arians to return. Thereafter, the term homoousios disappears.

In the 340s, the Western Church, which up then was on the periphery of the Controversy, became involved by taking the side of the Nicenes who had been previously deposed by the Eastern Church. This brought a new phase to the Controversy. It also became an East/West dispute.

In the 350s, Emperor Constantine forced the Western Church to accept the Eastern (Arian) view.

In the 360s-370s, the church maintained mostly the Arian doctrine accepted in 360. However, in 380, Emperor Theodosius, through the Edict of Thessalonica, made Nicene Christianity (which later developed into the Trinity doctrine) the sole legal religion of the Roman Empire (see here).

So, in total, the Controversy lasted for 62 years. When it came to an end, all those who took part at the beginning were already dead.

Traditional Account

| The traditional account of the Origin of the Trinity doctrine is a complete travesty. |

The Trinitarian and leading scholar on that Controversy, Bishop R.P.C. Hanson, stated that the traditional account of that Controversy is a complete travesty:

The “conventional account of the Controversy, which stems originally from the version given of it by the victorious party, is now recognised by a large number of scholars to be a complete travesty.” (Hanson).

“If Athanasius’ account does shape our understanding, we risk misconceiving the nature of the fourth-century crisis” (Williams, 234).

Another prominent scholar and Professor of Catholic and Historical Theology, Lewis Ayres, confirms that the “older accounts (of the Arian Controversy) are deeply mistaken” (Ayres, 11).

Since the Arian Controversy was the birth of the Trinity doctrine, it is the traditional explanation of the Origin of the Trinity doctrine that is “a complete travesty.”

Revised Account

| New research and sources have altered the account of the Controversy fundamentally. |

“In the first few decades of the present (20th) century … seminally important work was … done in the sorting-out of the chronology of the controversy, and in the isolation of a hard core of reliable primary documents.” (Williams, 11-12)

“A vast amount of scholarship over the past thirty years has offered revisionist accounts of themes and figures from the fourth century.” (Ayres, 2)

On page xx (Roman numerals) of his book, Hanson lists several source documents that became accessible.

Books Quoted

| Therefore, this article is based on the writings of world-class scholars of the past 50 years. |

This article highlights several specific errors in the traditional account. It quotes primarily the following books:

Hanson – A lecture by R.P.C. Hanson in 1981 on the Arian Controversy.

Bishop R.P.C. Hanson

The Search for the Christian Doctrine of God –

The Arian Controversy 318-381, 1987

Archbishop Rowan Williams

Arius: Heresy and Tradition, 2002/1987

Lewis Ayres

Nicaea and its legacy, 2004

Ayres is a Professor of Catholic and Historical Theology

Cause

Existing Tensions

| Arius did not cause the Controversy. It was caused by existing tensions between theological traditions. |

In the traditional account, Arius was the founder and leader of a large and dangerous sect. That is not true. It was not a new controversy. It was caused by tensions between pre-existing theological traditions:

“There came to a head a crisis … which was not created by … Arius” (Hanson, XX).

In the older account, it was “the Church’s struggle against a heretic and his followers.” Now we know that it was “tensions between pre-existing theological traditions (which) intensified as a result of dispute over Arius” (Williams, 11).

“The views of Arius were such as … to bring into unavoidable prominence a doctrinal crisis which had gradually been gathering. … He was the spark that started the explosion. But in himself he was of no great significance.” (Hanson, xvii)

This also explains why the Controversy spread so quickly. In the traditional account, “the controversy spread because Arius was supported by wicked and designing bishops.” In reality, the Controversy spread so quickly because the opposing sides were already established when the fourth century began.

Arius

| Arius was part of the orthodox tradition, but deviated in some respects. |

In the traditional account, Arius was the founder of a novel heresy, known as Arianism. In reality, Arianism was the orthodox mainstream, and Arius was part of it. He continued to teach that the Son is the Father’s “subordinate though essential divine agent.” Rowan Williams described Arius as a conservative:

“Arius was a committed theological conservative; more specifically, a conservative Alexandrian.” (Williams, 175)

However, Arius did deviate from some aspects of the tradition. For example:

While Origen taught, contrary to the Logos theologians, that the Son always existed, Arius said that He did not always exist.

While the tradition taught that the Son was begotten from the being of the Father, Arius said that He was generated out of nothing. Arius’ view that Christ is a created being was consistent with the lower end of the spectrum of views before the Arian Controversy:

“The second-rate or third-rate writers of the period (before Nicaea)” even “present us unashamedly with a second, created god lower than the High God.” (Hanson’s lecture)

Arius was an extremist under the overall orthodox umbrella of subordination. For that reason, he was opposed by both Nicenes and Arians.

Alexander

| Alexander caused the Controversy by continuing a theology that was already rejected as heresy. |

This is an extremely important point. In the traditional account, Alexander and Athanasius, the main defenders of the Nicene view, continued the orthodox view. In reality, they believed that the Son is part of the Father. Consequently, the Father and Son are one single Person (hypostasis). (See here) This is similar to Sabellianism, which was rejected in the third century, for example, by a council in Antioch in 268.

Emperors Decided.

| What was new in the fourth century was that the emperors were the ultimate judges in doctrinal disputes. |

During the first three centuries, the church was persecuted. The last great persecution ended in 313, when Christianity was legalized. However, now that the emperor himself was a Christian, and since, in the Roman Empire, the emperors decided which religions and factions of religions to allow, the emperor was the ultimate authority in doctrine. The Controversy continued the same issues, but it was new in the sense that the emperor had to decide between the parties.

“The truth is that in the Christian church of the fourth century there was no alternative authority comparable to that of the Emperor.” (Hanson, 854)

“If we ask the question, what was considered to constitute the ultimate authority in doctrine during the period reviewed in these pages, there can be only one answer. The will of the Emperor was the final authority.” (Hanson, 849)

“Throughout the controversy, everybody … assumed that the final authority in bringing about a decision in matters doctrinal was not a council nor the Pope, but the Emperor.” (Hanson)

Consequently, the emperor effectively was the head of the church:

“Simonetti remarks that the Emperor was in fact the head of the church.” (Hanson, 849) Show More

Core Issue

Subordination

| ‘Subordinate’ was the orthodox view when the Controversy began. |

In the traditional account, the orthodox view when the Controversy began in 318 was that the Son is equal to the Father. That is false. Nobody in the first three centuries claimed that the Son is the Ultimate Reality. All sides agreed that the Son is subordinate to the Father. To explain:

In the second century, after Christianity became Gentile-dominated, while Christianity was still outlawed and persecuted, the Christian Apologists identified the Son of God with the Logos or Nous of Greek philosophy. In that philosophy, the Logos was a subordinate Intermediary between the high God and the physical world. As such, the Apologists explained the Son as “a subordinate though essential divine agent” of the Father. In their view, known as Logos theology, the Son is divine, but not as divine as the high God. (See here.)

In the third century, Logos-theology was opposed by Sabellianism, but Sabellianism was formally rejected at church councils. Consequently, Logos theology remained the standard teaching of the church right into the fourth century:

Hanson describes Logos-theology as the “the main, widely-accepted, one might almost say traditional framework for a Christian doctrine of God well into the fourth century … the basic picture of God with which the great majority of those who were first involved in the Arian Controversy were familiar and which they accepted” (Hanson).

The “conventional Trinitarian doctrine with which Christianity entered the fourth century … was to make the Son into a demi-god … a second, created god lower than the High God” (Hanson).

Tertullian (155-220) was one of the Logos theologians. He is today regarded as an early Trinitarian. However, in his view, “The Father is the entire substance, but the Son is a derivation and portion of the whole” (Against Praxeas, Chapter 9). Therefore, he also described the Son as subordinate (see here).

So, subordinationism was the orthodox view of Christ when the Arian Controversy began:

“’Subordinationism’, it is true was pre-Nicene orthodoxy” [Henry Bettenson, The Early Christian Fathers p. 239.]

“With the exception of Athanasius, virtually every theologian, East and West, accepted some form of subordinationism at least up to the year 355; subordinationism might indeed, until the denouement (end) of the controversy, have been described as accepted orthodoxy” (Hanson, xix).

| The Nicenes agreed that the Son is subordinate. |

It is often claimed that the Nicenes taught that the Son is equal to the Father. That is not true. For example:

Alexander and Athanasius taught that the Son is part of the Father and, therefore, subordinate to the Father.

The Cappadocian Fathers, later in the century, described the Son as being equal in terms of substance (ontologically), but still subordinate to the Father.

Therefore, whether or not the Son is subordinate was not the core issue in the Controversy.

Divinity

| All sides regarded the Son as divine. |

In the traditional account, the Controversy was over whether Jesus is God or a created being. This is false. The view that the Son is a created being was held by only a few. The standard Arian view was that the Son is a divine Being, subordinate to the Father. Therefore, whether or not the Son is divine was not the core issue in the Controversy.

Distinct

| The core issue in the Controversy was whether the Son of God is a distinct Person. |

Since the Controversy was caused by existing tensions, to understand what the dispute was about, one has to begin with the preceding century. An analysis of the views in the fourth and preceding centuries will show that the core issue was whether the Son is a distinct Being:

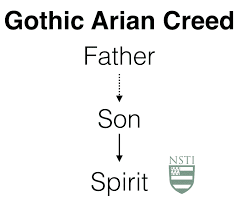

Arianism taught that the Son is a distinct Being. They argued that the Father and Son are two hypostases (two distinct existences).

The Nicenes argued that the Son is part of the Father (see here). Therefore, the Father and Son are a single Being: a single hypostasis, a single individual existence.

This can be seen in the following overview of the history:

While the Old Testament seems to present a single divine Being, the New Testament seems to present Jesus Christ as a second divine Being.

So, in the second century, while the Monarchians claimed that the Son and Father are a single Being or Person, Logos-theology argued that He is a distinct Being, subordinate to the Father.

In the early third century, Origen refined Logos-theology and Sabellius refined Monarchianism, but the core issue remained the same, whether the Son is a distinct Person:

Sabellius taught that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are three parts of a single Being (a single hypostasis), like man consists of body, soul, and spirit. Sabellius used the term homousios in his theology.

In the middle of the third century, there was a dispute between the bishops of Rome and Alexandria (both named Dionysius). Some Sabellians in Libya claimed that the Son is homoousios to the Father and complained to the Bishop of Rome about the Bishop of Alexandria, who had oversight over them. While Rome insisted that the Father, Son, and Spirit are one hypostasis, Alexandria maintained they are three. (The term ‘hypostasis’ is often translated as meaning ‘person.’ It means an individual existence.)

A church council in 268 in Antioch condemned Paul of Samasota, apparently for teaching that the Father and Son are a single hypostasis and that Jesus Christ did not exist before His human birth. That council also condemned the use of the word homoousios. For a further discussion, see here.

In the dispute between Arius and Alex. In the traditional account, Arius developed a novel heresy. However, in a recent book on Arius, Rowan Williams described him as a conservative Alexandrian. In Alexandria, he attempted to defend the traditional view, for example, as was taught by the Bishop of Alexandria (Dionysius) when Arius was born.

That was also the dispute between the ‘Nicenes’ and ‘Arians’ in the 340s, as shown by the Creeds of 341 and 343.

Arianism Dominated

Arianism Defined

Since all agreed that the Son is divine but subordinate to the Father, Arianism may be defined as the view that the Son is a distinct divine Being, subordinate to the Father.

Beginning

| Arianism, as defined, dominated at the beginning of the fourth century. |

In the traditional account, the Trinity doctrine was already established as orthodoxy when the fourth-century Controversy began. Show More

Defined this way, Arianism was the orthodox view when the Controversy began:

As stated above, in the third century, Sabellianism was rejected as a heresy. Consequently, Logos-theology, in which the Son is a distinct subordinate divine Being, remained the orthodox view into the fourth century. (See here for a detailed discussion of the orthodox view when the Controversy began.)

Nicene Council

| The Nicene Creed is anti-Arian, but the emperor forced the Nicene Council to accept it. |

One indication that the Nicene Creed is anti-Arian is that it explicitly states that the Father and Son are a single hypostasis. Another is that it uses the term homoousion to say that the Son is of the same substance as the Father. In the conventional account, homoousios is “the key word of the Creed” (Beatrice). Show More

Homoousion was a Sabellian term. Only Sabellians preferred it before and at Nicaea:

Before Nicaea, it was used by Sabellius himself, the Egyptian Sabellians, and the Bishop of Rome in the middle of the third century, and by Paul of Samosata about a decade later. The term for formally rejected by a church council in 268.

At Nicaea, the emperor proposed the term because he saw that the Sabellians, with whom Alexander allied, preferred this term.

Most delegates opposed the term, but it was accepted because Emperor Constantine forced the Nicene Council to accept it. Show More

Eusebius of Caesarea, the most respected theologian at Nicaea and the leader of the ‘Arians,’ afterwards rationalized his acceptance of the term in his letter to his home church (See here).

Ecumenical Councils

| The so-called ecumenical councils were the tools the emperors used to force the Church. |

In the conventional account, the councils of 325 and 381 were ecumenical, meaning that they were meetings of church authorities from the whole ‘world’ (oikoumene) that secures the approval of the whole Church.

In reality, the so-called ecumenical councils were the tools by which the emperors ruled over the church:

“The general council was the very invention and creation of the Emperor. General councils, or councils aspiring to be general, were the children of imperial policy and the Emperor was expected to dominate and control them. Even Damasus (bishop of Rome) would have admitted that he could not call a general council on his own authority.” (Hanson, 855)

One indication of this is that, at both ‘ecumenical’ councils, representatives of the emperor presided over the meetings:

“Ossius, as the Emperor’s representative, presided at Nicaea.” (Hanson, 154, cf. 148, 156) He was a bishop, but he presided in his capacity as the emperor’s “agent.” (Hanson, 190)

When Theodosius came to power, he immediately exiled the ruling Homoian bishop of the capital city and appointed Gregory of Nazianzus in his place. Gregory presided over the 381-council but, for some unknown reason, resigned. Thereafter, Emperor Theodosius assigned Nectarius, an unbaptized civil official, as presiding officer.

Post-Nicaea Correction

| In the decade after Nicaea, the church reversed the decisions of the Nicene Council. |

In the traditional account, the “pious design” of Emperor Constantine, who “called a general Council at Nicaea which drew up a creed intended to suppress Arianism and finish the controversy,” was frustrated “owing to the crafty political and ecclesiastical engineering of the Arians.” (Hanson).

In reality, Constantine had a change of heart. In the decade after Nicaea, he allowed all exiled ‘Arians’ to return and allowed the Church to exile all leading pro-Nicene theologians. (See here). Thereafter, the term homoousios disappeared from the Controversy for more than 20 years. Show More

350s

In the 350s, Athanasius brought it back into the Controversy, causing the ‘Arians’ to divide into the different ‘sides’ described above. Each of these ‘sides’ represented a different perspective on the term homoousios, showing that this term was at the heart of the Controversy.

Theodosius

Theodosius succeeded in putting an end to the Controversy, at least within the Roman nation, because he made a formal Roman law to outlaw Arianism, which he followed up with severe persecution.

Nicene Theology

| Nicene theology broke away from the tradition. |

It was Nicene theology, therefore, claiming that the Son is equal to the Father, that deviated from the “tradition” of the pre-Nicene orthodoxy. For example:

“What the fourth-century development did was to destroy the tradition of Christ as a convenient philosophical device … In this respect at least … they rejected the allurements of Greek philosophy.” (Hanson)

“In the place of this old but inadequate Trinitarian tradition the champions of the Nicene faith substituted another.” (Hanson)

Sabellianism

| Nicene theology is sabellianism. |

In the traditional account, Nicene theology differs from Sabellianism. However, there are several indications that the pro-Nicenes were Sabelians or at least skirted Sabellianism:

Both taught that the Father and Son are a single hypostasis (Person).

Nicenes allied with the Sabellians. Alexander allied with the Sabellians at Nicaea, and, in the following decade, Athanasius allied with the Sabellian Marcellus.

The Council of Rome formally declared Marcellus (the main Sabellian of the time) orthodox. Show More

Both the Nicene Creed and the Western manifesto of 343 condone Sabellianism. The latter is very important because it was probably the only instance where the Nicenes could express their views without interference from the emperors:

“The anathema of Nicaea against those who maintain that the Son is of a different hypostasis or ousia from those of the Father and the emphatic identification of the ousia and hypostasis of the Father and the Son in the Western statement after the Council of Sardica only seemed to support” “a condoning of Sabellianism.” (Hanson) Show More

The Arians of the time did accuse the Nicenes of Sabellianism:

“Up to the year 357, the East could label the West as Sabellian and the West could label the East as Arian with equal lack of discrimination and accuracy.” (Hanson) In other words, the East labelled the West as Sabellian.

The Nicenes supported Sabellians for appointment as bishops:

In the year 375 “the Pope, Damasus, and the archbishop of Alexandria, Peter, were supporting Paulinus of Antioch, a Sabellian heretic, and Vitalis, an Apollinarian heretic, against Basil of Caesarea, the champion of Nicene orthodoxy in the East!” (Basil was the first of the three Cappadocians.) (Hanson)

It was not a ‘Arian’ Contoversy. It was a Sabellian Controversy.

Evolved

| The Nicene Creed does not reflect the modern Trinity doctrine. |

In the traditional account, the Nicene Creed of 325 describes God as a Trinity. This is not true. For example:

(a) Like many previous creeds, the Creed identifies the Father as the “one God” in contrast to Jesus Christ, who is identified as the “one Lord.” Show More

(b) The core of the Trinity doctrine is that God is one Being (substance; ousia in Greek) but three Persons (hypostases). But the Nicene Creed describes the Father and Son as a single hypostasis. Show More

(c) The Creed does not describe the Holy Spirit as God or as equal to God or as one substance with God:

“Of course the theologians of the side which was ultimately victorious included the Holy Spirit in the Trinity. In a sense this was an afterthought, because the theme of the Son occupied the screen, so to speak, right up to the year to the year 360.” (Hanson)

Athanasius

| Athanasius displayed violence and unscrupulousness towards his opponents in Egypt. |

Athanasius, who is regarded by many as the hero of the ‘Arian’ Controversy, was exiled five times by four different emperors, spending almost half of his 45 years as bishop of Alexandria in exile (Blue Letter). In the conventional account, “supporters of the orthodox point of view such as Athanasius of Alexandria … were deposed from their sees on trumped-up charges and sent into exile.”

But Hanson stated:

“The most serious initial fault was the misbehavior of Athanasius in his see of Alexandria. Evidence which has turned up in the sands of Egypt in the form of letters written on papyrus has now made it impossible to doubt that Athanasius displayed a violence and unscrupulousness towards his opponents in Egypt which justly earned the disgust and dislike of the majority of Eastern bishops for at least the first twenty years of his long episcopate.” (Hanson)

Arianism

Misnomer

| Arius was not important. The Anti-Nicenes did not follow him. Therefore, the term “Arian” is a serious misnomer. |

In the traditional account, all opponents of the Nicene Creed were followers of Arius and may be called ‘Arians.’ However, Arius was not important (see here):

“In himself he was of no great significance” (Hanson, xvii).

Arius was only of some relevance for the first 7 of the 62 years of Controversy. The later so-called ‘Arians’ did not regard him as a particularly significant writer, and they did not follow him. They never quoted him. In fact, they opposed him. He did not leave behind a school of disciples, and he was not the leader of the ‘Arians’. He was an extreme example of a wider theological trajectory.

Many supported Arius, not because they accepted all his views, but because they regarded the views of bishop Alexander as even more dangerous:

Eusebius of Caesarea “thought the theology of Alexander a greater menace than that of Arius.” (Williams, 173)

The term ‘Arian’, therefore, is a serious misnomer.

“The expression ‘the Arian Controversy’ is a serious misnomer” (Hanson, xvii-xviii)

“This controversy is mistakenly called Arian.” (Ayres, 13)

Arian Factions

| There were not just two sides to the Controversy. Both the Arians and Nicenes were divided into factions. |

In the traditional account, “the bishops and theologians taking part in the controversy as falling simply into two groups, ‘orthodox’ and’ Arian’.” But Hanson says this “is a grave misunderstanding and a serious misrepresentation of the true state of affairs.” (Hanson Lecture) In reality, most of those who opposed the Nicene Creed also opposed Arius’ theology. The Arians were divided into various groups with respect to the term homoousios:

Different Substance – The Heter-ousians were the extreme Arians, also called the Neo-Arians. They claimed that the Son is of a “different substance” than the Father. This is what Arius had taught, but the Neo-Arians developed this into a much more sophisticated theology.

Similar Substance – The Homoi-ousians became fairly dominant during the Controversy. They rejected the view that the Son’s substance is the same as the Father’s, for the Father alone exists without cause. But they also argued that if the Son was “begotten” from the Father, His substance must be similar to the Father’s.

Like the Father – The Homo-ians, like good Protestants, maintained that it is arrogance to speculate about the substance of God because the Bible does not say anything about His substance. The most that they were willing to say is that the Son is like the Father because that is what the Scripture teaches (e.g., Col 1:15). This view was accepted at the Council of Constantinople in AD 359 (not 381) and, when Theodosius became emperor in AD 379, the bishop of the capital was a Homoian.

This shows that the Controversy at this time (the 350s) focused on the word Homoousion (same substance). Rowan Williams confirms this when he says that “Arianism … was … (an) uneasy coalition of those hostile to … the homoousios in particular” (Williams, 166).

Nicene Factions

The Nicenes were also divided into two groups with respect to the interpretation of the term homoousios:

The Western Nicenes, including the Sabellians and Athanasius, understood homoousios as meaning ‘one substance.’

The Eastern Nicenes (the Cappadocians) understood the Father and Son as two distinct substances that are the same in all respects.

Consequently, “Arianism,’ throughout most of the fourth century, was in fact a loose and uneasy coalition of those hostile to Nicaea in general and the homoousios in particular” (Williams, 166).

Athanasius Coined

| Athanasius coined the misleading term ‘Arian’ to insult his opponents. |

But then the question arises, why does the traditional account of the Controversy group all anti-Nicenes under the term ‘Arian’? The only reason is that Athanasius invented the term to falsely label his opponents with a theology that was already rejected by a formal church council. Athanasius did this to defend himself because he was accused of being a Sabellian:

“At the Council of Serdica in 343 one half of the Church accused the other half of being ‘Arian’, while in its turn that half accused the other of being ‘Sabellian’.” (Hanson, xvii)

After the Nicene side came out victorious, the Roman Church continued Athanasius’ practice. (For more details, see here.)

| Arianism is a system worth studying. |

In the traditional account, ‘Arianism” is “a crude and contradictory system.” (Gwatkin (c. 1900) – RW, 10). Harnack (1909) describes Arius’ teaching as “novel, self-contradictory and, above all, religiously inadequate” (Williams, 7). However, Archbishop Rowan Williams, after writing a recent book about Arius, concluded:

Arius is “a thinker and exegete of resourcefulness, sharpness and originality.” (Williams, 116) Show More

Philosophy

| All theologians used philosophy, but Arianism reduced reliance on philosophy. |

In the conventional account, Arius and ‘Arianism’ were almost as much motivated by Greek philosophy as by the Bible. Show More

In reality, Arius did not introduce philosophy into theology: He and all Christians of that time inherited a Christology that is based on pagan philosophy. As discussed, the Christian Apologists of the preceding centuries explained the Son of God as the Logos of Greek philosophy. As Hanson stated:

“Arianism … does present the Son as in effect a demi-god, even though the antecedents of this doctrine are not to be found in pagan religion nor directly in Greek philosophy but in various theological strands to be detected in Christian theology before the fourth century.” (Hanson)

Therefore:

“We misunderstand him completely … if we see him as primarily a self-conscious philosophical speculator. … Arius was by profession an interpreter of the Scriptures” (Williams, 107-108). Show More

Furthermore, Arianism reduced the influence of Greek philosophy. For example, in AD 359, at a council in Constantinople, the church accepted adopted a Homoian creed in which the words from Greek philosophy (ousia, homoousios, and hypostasis) are forbidden. This version of Christianity dominated the church until Theodosius became emperor.

While Arianism is often accused of corrupting theology with philosophy, the shoe is on the other foot. The three Cappadocian fathers were deeply influenced by philosophy:

“Before the advent of the Cappadocian theologians there are two clear examples only of Christian theologians being deeply influenced by Greek philosophy.” (Hanson, 862) “The Cappadocians, however, present us with a rather different picture. … They were all in a sense Christian Platonists.” (Hanson, 863) Show More

All theologians used the terms and concepts of Greek philosophy:

“The development of the doctrine of the Trinity was carried out in terms which were almost wholly borrowed from the vocabulary of late Greek: hypostasis, ousia … and so on” (Hanson).

“The fourth-century Fathers thought almost wholly in the vocabulary and thought-forms of Greek philosophy” (Hanson).

“The case was not merely that the theologians of the fourth century used Greek words. They thought Greek thoughts.”

For a further discussion, see here.

Theodosius

| It was an emperor, not an ecumenical council, that put an end to the Controversy. |

In the traditional account, the Council of Constantinople in the year 381 put an end to that Controversy. In reality, the Controversy was brought to an end by a Roman law (See here):

Theodosius was declared Emperor and Augustus (i.e., equal with, not subordinate to, Gratian) on 19 January of the year 379.

Already in the year before that church council, in February 380, Emperor Theodosius issued the Edict of Thessalonica, which made Western Nicene theology the official religion of the Roman Empire. This Roman edict (not a church council) ordered all Romans (not only Christians) “to believe ‘the single divinity of Father, Son and Holy Spirit within … an equal majesty and … Trinity’” (Hanson, 804).

That same edict outlawed all other forms of Christianity. Theodosius described all who do not conform as “foolish madmen.” “They will suffer … the punishment of our authority.”

In November of the same year, he entered Constantinople (the capital of the empire) and instantly drove out the ruling Homoian bishop, appointed one of the three Cappadocians, and also chased the ‘Arian’ Lucius out of Alexandria. (Hanson, 804-5)

In January 381, still before the ‘Ecumenical’ Council, Theodosius issued an edict saying that no church was to be occupied for worship by any heretics, and no heretics were to gather together for worship within the walls of any town. (Hanson, 805)

Only after these events did he summon the so-called ‘ecumenical’ Council of Constantinople of the year 381. But only pro-Nicenes were allowed to attend (Hanson, 805-6), and the emperor appointed an unbaptized government official to chair the meeting.

It amazes me that people regard this as a valid and important church council, even after non-Nicene clergies have been outlawed and exiled.

Later in 381, he decreed that all non-Nicene churches must be delivered to Trinitarian bishops. (Boyd)

The Arian Controversy, therefore, was brought to an end by the command of the Roman Emperors.

However, Theodosius only put an end to Arianism within the Roman Empire. The other European nations converted to Christianity before Theodosius came to power and, therefore, were ‘Arians.’ After Nicene theology became the Roman State Church, they remained ‘Arian,’ and when they took control of the Western Empire in the fifth century, Arianism again dominated Europe.

Role of Emperors

| In the Roman Empire, the emperors were the ultimate judges in doctrinal disputes. |

In the traditional account, the emperors during the 50 years after Nicaea forced the church to oppose the Nicene Creed (Hanson). Show More

This is true, but what this omits to say is that, as discussed above, throughout the Controversy, the emperor always had the final say in doctrinal disputes. When the emperor was an Arian, the church was Arian, but when the emperor supported the Nicene side, the church followed. For all practical purposes, the emperor was the head of the church. Church and state were united (Boyd). For example:

Constantine, in AD 325, insisted on the inclusion of the word homoousios in the Creed but softened towards Arianism and was baptized on his deathbed by the Arian leader, Eusebius of Nicomedia.

Constantius (Constantine’s son, 337-361) was a Homoian. In 359, the Western bishops met in Ariminum and accepted a Homo-ian creed. But the eastern bishops, who met in Seleucia, accepted a Homoi-ousian creed. Emperor Constantius did not accept this outcome and called for another council in the same year in Constantinople, where both the eastern and western bishops were present. In the initial debate, the Heter-ousians defeated the Homoi-ousians. However, Constantius rejected this decision as well and exiled some of the delegates. Thereafter, the council agreed to the Homo-ian creed that was accepted at Ariminum, with minor modifications.

Valens (364-378) also was a Homoian. He used the power of the state to promote his theology. He made sure that the right person was installed as archbishop, banished and imprisoned pro-Nicene clergy, put them to forced labor, and subjected them to taxes from which anti-Nicenes were exempt. But, Hanson states, “his efforts at persecution were sporadic and unpredictable.” (Hanson, 791-792)

Theodosius (379-395), as already discussed, adopted Wester Nicene theology. He was the first to create a law requiring conformance to a Christian practice and took persecution to a different level. He brutally eliminated all other versions of Christianity from the empire.

Justinian of the Eastern Roman Empire, in the sixth century, subjected those ‘Arian’ kingdoms and set up the Byzantine Papacy through which the Eastern Emperors ruled the ‘Arians’ in the west for two centuries. The dominance of the Eastern Empire, through the Roman Church, eventually caused all these Arian kingdoms to convert to Nicene theology. (See – here.)

Conclusion

This article has shown that the traditional account of the Controversy is diametrically opposed to the historical reality. This information has been available for at least the past 50 years, but it remains limited to scholarly books and articles. Why do the Church and sources such as Wikipedia continue to teach the traditional account? As Williams indicated, one reason is that the prejudice caused by the long history of ‘demonizing’ Arius is extraordinarily powerful (Williams, 2). Furthermore, this history casts doubt on both the origin and the nature of the Trinity doctrine, which is regarded by many as the foundational doctrine of the Church:

Firstly, it shows that Arianism dominated during at least the first five centuries. However, in the late fourth century, the Roman Empire made Nicene Christianity its sole religion and, during the Byzantine Papacy (6th to 8th centuries), forced the other nations to also accept Nicene theology (see here). The so-called ecumenical councils of the fourth century were meetings called and dominated by the emperors to force the church to implement the emperors’ decisions.

Secondly, it shows that the Trinity doctrine is the child of ancient Sabellianism, teaching that the Father, Son, and Spirit are a single Being with a single mind. The explanation that they are three Persons is an attempt to make this doctrine more acceptable, but if the Father, Son, and Spirit share a single mind and will, the term ‘three Persons’ is misleading. (See here for a discussion of the Trinity doctrine.)

After the Roman Empire finally fragmented, the Roman Church survived as a distinct entity and grew in power to become the Church of the Middle Ages.

Today, the Roman Empire no longer exists, but its official religion – a symbol of its authority – continues to dominate Christianity. It is regarded as the most important doctrine of the church. Non-Trinitarians are regarded as non-Christians.

But the church as such never adopted the Trinity Doctrine. It was the other way round. The Roman Empire adopted the Trinity Doctrine and systematically exterminated all opposition.

Other Articles

-

-

- Arian Controversy – All articles

- Arius – Who was he? What did he believe?

- Nicene Creed – Who created it? What does it say?

- Homoousios – What does it mean?

- Fourth-Century ‘Arianism’

- Is Jesus the Most High God?

- All articles on this website

-

In the first three centuries after Christ, the Roman Empire persecuted the church. In the fourth century, the church was first legalized (AD 313) and later became the official religion of the Roman Empire (AD 380). During that period, a controversy raged in the church with respect to the nature of Christ. The emperors could not allow disunity in the church because a split in the church could split the entire empire. The emperors, therefore, forced the church to formulate creeds, and, true to the nature of the empire, banish church leaders who were not willing to accept the creeds.

In the first three centuries after Christ, the Roman Empire persecuted the church. In the fourth century, the church was first legalized (AD 313) and later became the official religion of the Roman Empire (AD 380). During that period, a controversy raged in the church with respect to the nature of Christ. The emperors could not allow disunity in the church because a split in the church could split the entire empire. The emperors, therefore, forced the church to formulate creeds, and, true to the nature of the empire, banish church leaders who were not willing to accept the creeds.

The purpose of this article is to analyze what Arianism believed in the fourth century. Some of the historical facts mentioned in this article are described in more detail in other articles.

The purpose of this article is to analyze what Arianism believed in the fourth century. Some of the historical facts mentioned in this article are described in more detail in other articles. Today, Trinitarians regard

Today, Trinitarians regard  The fifty-year Arian period after Nicaea resulted in numerous synods, including at

The fifty-year Arian period after Nicaea resulted in numerous synods, including at  Ulfilas’ Arianism – What he believed is perhaps a good reflection of the Arianism that was generally accepted in the church between Nicaea (325) and Constantinople (381). He wrote:

Ulfilas’ Arianism – What he believed is perhaps a good reflection of the Arianism that was generally accepted in the church between Nicaea (325) and Constantinople (381). He wrote: Subject and obedient – Ulfilas furthermore believed “in one Holy Spirit, the illuminating and sanctifying power … Neither God nor lord/master, but the faithful minister of Christ; not equal, but subject and obedient in all things to the Son.” That the Holy Spirit is “neither God nor lord” implies that Ulfilas did not think of the Holy Spirit as a Person, but as a power, and a power that is subject and obedient in all things to the Son.

Subject and obedient – Ulfilas furthermore believed “in one Holy Spirit, the illuminating and sanctifying power … Neither God nor lord/master, but the faithful minister of Christ; not equal, but subject and obedient in all things to the Son.” That the Holy Spirit is “neither God nor lord” implies that Ulfilas did not think of the Holy Spirit as a Person, but as a power, and a power that is subject and obedient in all things to the Son.