Summary of this article

In the first three centuries after Christ, the Roman Empire persecuted the church. In the fourth century, the church was first legalized (AD 313) and later became the official religion of the Roman Empire (AD 380). During that period, a controversy raged in the church with respect to the nature of Christ. The emperors could not allow disunity in the church because a split in the church could split the entire empire. The emperors, therefore, forced the church to formulate creeds, and, true to the nature of the empire, banish church leaders who were not willing to accept the creeds.

In the first three centuries after Christ, the Roman Empire persecuted the church. In the fourth century, the church was first legalized (AD 313) and later became the official religion of the Roman Empire (AD 380). During that period, a controversy raged in the church with respect to the nature of Christ. The emperors could not allow disunity in the church because a split in the church could split the entire empire. The emperors, therefore, forced the church to formulate creeds, and, true to the nature of the empire, banish church leaders who were not willing to accept the creeds.

Arianism was named after Arius.

We are not sure what Arius taught, for his books were destroyed after Nicaea, and we cannot trust what his opponents wrote about him. For example, Athanasius claimed that Arius said that “there was a time when the Son was not,” but below we quote Arius saying that the Son existed “before time.”

‘Arianism’ dominated the church for 50 years.

Many erroneously understand the Nicene Creed of 325 to say that the Son is equal to the Father but, after 325, the consensus in the church was that the Son is subordinate to the Father. What the church believed at the time was different from what Arius believed, but it is practice today to describe anything that is not perfectly consistent with the Trinity doctrine as Arianism. Therefore, since, in the Trinity doctrine, the Son is co-equal to the Father, it is common for people to the refer to the belief in the fourth century, that the Son is subordinate to the Father, as Arianism.

This ‘Arianism’ remained the dominant view in the church for the next 50 years. During those fifty years, this ‘Arianism’ evolved and divided into a number of branches. It is, therefore, important to understand what the church believed after the intense debates of those years.

God and theos

Today, we use the modern word “God” as the proper name of the One who exists without a cause. The ancient Greek word, in the Bible and other ancient documents, such as the Nicene Creed, that is translated as “God” is theos. But theos is the common name for the Greek gods and means “god” in Eglish. When it refers to the One who exists without a cause, it is correctly translated as “God.” In instances where theos refers to Jesus, it can be translated as “God” only if one assumes the Trinity doctrine. In Arianism, in which only the Father is the One who exists without a cause, theos, when it describes Jesus, or to any being other than the Father, must be translated as “god.” See the article – theos – for a further discussion.

What the Arian church believed

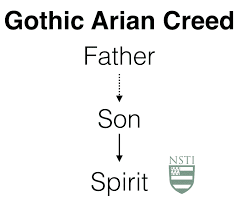

In Arianism:

The Father is the “only one God.” In contrast to the Son who is the “begotten,” the Father is “the unbegotten,” which means that He exists without a cause and, therefore, is the ultimate Cause of all else.

The Son is our god, but the Father is His god. God created all things through the Son. Since the Son was “begotten” by the Father, which is understood to mean that He was born of the Being of the Father, He was not created but, nevertheless, subordinate to the Father.

The Holy Spirit is not a Person, but as a power; subject to the Son.

– END OF SUMMARY –

Purpose of this article

The Metamorphosis of the Church

The fourth century was a remarkable period in which the church changed from being PERSECUTED to being the OFFICIAL STATE RELIGION of the Roman Empire. For all practical purposes, the church became part of the state and, as will be explained, the emperor became the head of the church. Adopting the character of the empire, the church changed from being persecuted to persecuting church leaders who do not accept the official church decrees.

Arian Controversy

In that fourth century, a huge controversy raged with respect to the NATURE OF CHRIST. The Nicene Creed—formulated in the year 325 at the city of Nicaea—described the Son as “true theos from true theos” and as of the “same substance” as the Father. Many today interpret these phrases as that the Son is EQUAL to the Father. The article on the Nicene Creed shows that this interpretation is wrong and that that Creed described the Son as subordinate to the Father.

After the creed was formulated in the year 325, for the next 50 years, the church was dominated by teachings in which the Son is SUBORDINATE to the Father. This Arian period was brought abruptly to an end when Theodosius became emperor in the year 380. He was an ardent supporter of Nicene Christology and, on ascending the throne, IMMEDIATELY declared Arianism to be illegal and Nicene Christology to be THE ONLY religion of the empire. He then replaced the Arian church leadership with Nicene leaders.

Purpose of this article

The purpose of this article is to analyze what Arianism believed in the fourth century. Some of the historical facts mentioned in this article are described in more detail in other articles.

The purpose of this article is to analyze what Arianism believed in the fourth century. Some of the historical facts mentioned in this article are described in more detail in other articles.

Conflicting evidence in the Bible

To understand the war between Nicene Christology and Arianism, we must appreciate the seemingly conflicting evidence in the Bible about the nature of Christ. Many Bible statements describe Him as equal with the Father, but many others imply that He is subordinate to God, for example:

| EQUAL | SUBORDINATE |

| He “upholds all things by the word of His power” (Heb 1:3) has “life in Himself” (John 5:26) sent the Holy Spirit to His disciples (Luke 24:49), is “the first and the last” (Rev 1:17) and owns everything which the Father has (Matt 11:27). “All things have been created through Him” (Col 1:16) and “all will honor the Son even as they honor the Father” (John 5:23). In Him, all the fullness of Deity dwells in bodily form (Col 2:9). “At the name of Jesus, every knee will bow” (Phil 2:10). Only He knows the Father. (Matt 11:27) | Only the Father knows the “day and hour” of His return (Matt 24:26). Everything which the Son has, He received from the Father, including to have “life in Himself” (John 5:22, 26). The Father sent Him and told Him what to say and do (John 7:16). The NT consistently makes a distinction between Jesus and God (e.g., Philemon 1:3). For example, Jesus is today at the right hand of God. The “one God” and “the only true God” is always the Father (1 Cor 8:6; 1 Tim 2:5; Eph 4:4-6; John 17:3). The Father is His God and He prayed to the Father. (Rev 3:12; John 17; Acts 7:56). |

What Arius believed about Christ

Arius

The words Arian and Arianism are derived from the name of Arius (c. 250–336); a church leader who had significant influence at the beginning of the fourth century. His teachings initiated the Arian controversy and Emperor Constantine called the council at Nicaea specifically to denounce His teachings.

We are not sure what Arius taught. After Nicaea in 325, the emperor gave orders that all of Arius’ books be destroyed and that all people who hide Arius’ writings, be killed. Very little of Arius’ writings survived, and much of what did survive are quotations selected for polemical purposes in the writings of his opponents. Reconstructing WHAT Arius actually taught, and—even more important—WHY, is, therefore, a formidable task. There is no certainty about the extent to which his teachings continued those of church fathers in previous centuries.

Letter to Eusebius

We have a brief statement of what Arius believed in a letter to the Arian archbishop of Constantinople; Eusebius of Nicomedia (died 341). He wrote as follows:

We say and believe …

that the Son is not unbegotten,

nor in any way part of the unbegotten;

and that he does not derive his subsistence from any matter;

but that by his own will and counsel

he has subsisted (existed) before time

and before ages as perfect as God,

only begotten and unchangeable,

and that before he was begotten, or created, or purposed, or established, he was not.

For he was not unbegotten.

We are persecuted because we say

that the Son has a beginning

but that God is without beginning.

(Theodoret: Arius’s Letter to Eusebius of Nicomedia, translated in Peters’ Heresy and Authority in Medieval Europe, p. 41)

Brief reflections on Arius’ view

The Son is not unbegotten,

nor in any way part of the unbegotten.

“Unbegotten” is how the ancients described the Being who exists without a cause (the Father). Since the Son is begotten, Arius argued that He is not part of that which exists without a cause. For Arius, only the Father is unbegotten.

He does not derive his subsistence from any matter.

| ARIUS | INTERPRETATION |

| NOT UNBEGOTTEN The Son is not unbegotten, nor in any way part of the unbegotten. |

“Unbegotten” is how the ancients described the Being who exists without a cause. Since the Son is begotten, Arius reasoned that He is not part of that which exists without a cause. For Arius, only the Father is unbegotten. |

| ONLY BEGOTTEN He does not derive his subsistence from any matter. |

The phrase “only begotten” identifies the Son as unique. There is no other like Him. “Begotten” indicates that His being came from the being of the Father. He was not created from other matter. |

| BEFORE TIME By his own will and counsel he has subsisted before time and before age. |

He existed as an independent Person with His own will; distinct from the will of God. He was begotten by God before time began. |

| PERFECT as perfect as God … unchangeable |

This shows the extremely high view which Arius had of the Son. Created beings change over time due to influences, but God and the Son are “unchangeable.” |

| HE WAS NOT. Before he was begotten, or created, or purposed, or established, he was not. The Son has a beginning but God is without beginning. |

Firstly, here, Arius indicates that he does not know what it means that the Son was begotten. Nevertheless, since He was is begotten, or created, or purposed, or established, He exists by the will of God (the Father) and “was not” before He was “begotten.” |

Arius seems to contradict himself. Above, he wrote that the Son “subsisted before time.” But he also wrote that the Son “was not” before He was begotten and that the Son “has a beginning.” It is a pity that we do not have Arius’ book that he can explain himself. Below, I propose how these statements can be reconciled.

A time when the Son was not

In the fourth century, Athanasius was the arch-enemy of Arianism and the great advocate of the homoousian (Nicene) theology. He quoted Arius as saying:

“If the Father begat the Son,

then he who was begotten

had a beginning in existence,

and from this, it follows

there was a time when the Son was not.”

Today, this quote by Athanasius is quite famous and is still used to characterize Arius’ teaching. But Arius wrote to Eusebius—in the quote above—that the Son existed “before time.” This seems to contradict what Athanasius wrote. We do not know whether Arius really wrote “there was a time when the Son was not” or whether this was a straw man created by Athanasius.

Today, Trinitarians regard Athanasius of Alexandria as a hero who stood for ‘the truth’ when ‘the whole world’ was Arian. Athanasius is counted as one of the four great Eastern Doctors of the Church in the Catholic Church.

Today, Trinitarians regard Athanasius of Alexandria as a hero who stood for ‘the truth’ when ‘the whole world’ was Arian. Athanasius is counted as one of the four great Eastern Doctors of the Church in the Catholic Church.

But in his day, he was a highly controversial character in his day. The church accused him of horrible crimes and exiled no less than five times. We are not able to judge either way today, but Athanasius was a prolific writer, and we can judge his spirit by his writings. For this purpose, listen to the following podcasts:

Assessing Athanasius and his Arguments

Athanasius’s On the Nicene Council

The Son had a beginning.

Eternal generation

In the Trinity doctrine today, the Son had no beginning but always existed with the Father. The Bible is clear that He is begotten by the Father but that is explained with the concept of eternal generation, namely that the Father always was the Father, that there never was a time that the Father was not the Father.

Arius, as quoted above, wrote that “the Son has a beginning but … God is without beginning.” But in the same statement, he wrote that the Son existed “before time and before ages.” Did Arius contradict himself? I wish we had Arius’ book to explain his own words but would like to propose the following explanation:

God created time. God is that which exists without a cause, and time exists because God exists. God, therefore, exists outside time, cannot be defined by time and is not subject to time. We cannot say that God existed ‘before time’, for the word “before” implies the existence of time, and there is no such thing as time before time. Therefore, I prefer to say that God exists ‘outside time’.

Since God created time, time had a beginning and is finite.

God created all things through the Son (e.g. 1 Col 8:6). Therefore, God created time through the Son. It follows that there never was a time when the Son did not exist. Arius, therefore, could validly write that the Son existed “BEFORE TIME.”

But, there exists an infinity beyond the boundaries of time. All the power and wisdom that we see reflected in this physical universe, comes out of that incomprehensible infinity beyond time, space and matter. In that infinity beyond time, Arius wrote, “THE SON HAS A BEGINNING.” But this is not a beginning in time, for there is no such thing as time in infinity.

This explains why Arius could both claim that the Son existed before time and had a beginning. If this was Arius’ thinking, he could not that written that “there was a time when the Son was not,” as Athanasius claimed.

Arianism evolved after Nicaea.

Forced unity

Under the stern supervision of the emperors, who demanded unity in the church to prevent a split in the empire, the fourth-century church fathers would not allow different views about Christ to co-exist within the church. The church’s view of Christ changed from time to time, but, nevertheless, it always formulated a view of Christ and, through persecution, forced all Christians to abide by the formal church doctrine.

Numerous synods

The fifty-year Arian period after Nicaea resulted in numerous synods, including at Serdica in 343, Sirmium in 358 and Rimini and Seleucia in 359. The pagan observer Ammianus Marcellinus commented sarcastically: “The highways were covered with galloping bishops.”

The fifty-year Arian period after Nicaea resulted in numerous synods, including at Serdica in 343, Sirmium in 358 and Rimini and Seleucia in 359. The pagan observer Ammianus Marcellinus commented sarcastically: “The highways were covered with galloping bishops.”

Numerous creeds

The best-known creed today is the Nicene Creed, but no fewer than fourteen further creeds were formulated between 340 and 360, depicting the Son as subordinate on the Father, e.g. the Long Lines Creed. Historian RPC Hanson lists twelve creeds that reflect the Homoian faith—one of the variants of Arianism—including the creeds of Sirmian (AD 357), Nice (Constantinople – 360), Akakius (359), Ulfilas (383), Eudoxius, Auxentius of Milan (364), Germinius, Palladius’ rule of faith (1988. The Search for the Christian Doctrine of God. Edinburgh: T&T Clark. pp. 558–559).

Arianism evolved.

During the fifty years between Constantine and Theodosius, Arianism was refined and nuanced, relative to what Arius believed. Consequently, although Arius’ views are important, it is far more important to understand what version of Arianism the church adopted after Arius’ views and the Nicene Creed were intensely debated in the decades following Nicaea.

The word “GOD” is ambiguous.

Before we discuss what Ulfilas wrote, we need to explain the difference between the word “God” and the words used in the New Testament:

Modern English

In modern languages, we differentiate between the words “god” and “God:”

When we use a word as a proper name, we capitalize the first letter. The word “God,” therefore, has a very specific usage: It is the PROPER NAME of one specific being; the One who exists without cause.

The word “god,” on the other hand, is a general category name used for all supernatural beings. It is even for human beings with super-human qualities.

Ancient Greek

The capital “G,” therefore, makes a huge difference. But, when the Bible was written, and also in the fourth century, there were no capital letters. Or, more precisely, the ancients wrote only in capital letters. The distinction between upper and lower case letters did not yet exist. According to the article on the timeline of writing in Western Europe, the ancients used Greek majuscule (capital letters only) from the 9th to the 3rd century BC. In the following centuries, up until the 12th century AD, they used the uncial script, which still was only capital letters. Greek minuscule was only used in later centuries.

Te Greek word theos

Since the word “God” is a name for one specific Being, the original New Testament does not contain any one word with the same meaning as “God.” The New Testament writers used the word theos, which is the same word that was used for the pantheon of Greek gods. The word theos, therefore, is equivalent in meaning to our modern word “god.” The word theos was also used for beings other than the one true God, even for “the god of this world” (2 Cor 4:4) and for human judges (John 10:35). Therefore, by describing the Father and the Son as “god,” the Bible and the fourth-century writers only indicated that the Father and the Son are immortal beings; similar to the immortal Greek gods. Consequently, the word “god” does not elevate the Father or the Son above the pagan gods.

The word “God,” in the translations of the New Testament and other ancient Greek writings, therefore, is an INTERPRETATION. When the translator believes that theos refers to the One who exists without a cause, theos is rendered as “God.” But when Paul wrote spoke about the theos of the pagan nations, the New Testament translates that as “god.” And when it translates theos, when it refers to Jesus, as “God,” it does that on the assumption of the Trinity doctrine.

True god

To indicate that the Unique Being is intended, the Bible writers added words such as “only,” or “true” or “one” to theos. But most often they simply added the definite article “the” to theos to indicate that the God of the Bible is intended.

In the Nicene Creed, both the Father and the Son are described as “true god.” The Bible never identifies the Son as “true god.” In the Bible, the “true god” is always the Father. For example:

“You, the only true God, and

Jesus Christ whom You have sent” (John 17:3)

“You turned to God from idols to serve a living and true God,

and to wait for His Son from heaven” (I Thess 1:9-10).

“So that we may know Him who is true;

and we are in Him who is true,

in His Son Jesus Christ.

This is the true God and eternal life” (1 John 5:20).

But then translators translate the Greek equivalent of “true god” as “true God.” Not only is this faulty translation, the word “true” in the phrase “true God” is SUPERFLUOUS, for there is only one “true God.” Since “God” already indicates the only true god, “true theos” should be translated either as “true god” or as “God.”

Ulfilas’ Christology

Germanic missionary – The Goth Ulfilas (c. 311–383) was ordained as bishop by the Arian Eusebius of Nicomedia and returned to his Gothic people to work as a missionary. He translated the New Testament into the Gothic language and is credited with the conversion of the Gothic peoples, which resulted in the wide-scale conversion of the Germanic peoples.

Ulfilas’ Arianism – What he believed is perhaps a good reflection of the Arianism that was generally accepted in the church between Nicaea (325) and Constantinople (381). He wrote:

Ulfilas’ Arianism – What he believed is perhaps a good reflection of the Arianism that was generally accepted in the church between Nicaea (325) and Constantinople (381). He wrote:

I, Ulfila … believe in

only one God the Father,

the unbegotten and invisible,

and in his only-begotten Son,

our lord/master and God,

the designer and maker of all creation,

having none other like him.

Therefore, there is one God of all,

who is also God of our God;

and in one Holy Spirit,

the illuminating and sanctifying power …

Neither God nor lord/master,

but the faithful minister of Christ;

not equal, but subject and obedient in all things to the Son.

And I believe

the Son to be subject and obedient in all things

to God the Father

(Heather and Matthews. Goths in the Fourth Century. p. 143 – Auxentius on Wulfila).

Discussion of Ulfilas’ Christology

The Father – Ultimate Cause of all else

Only one God

Ulfilas believed in “only one God,” who he identified as the Father. Actually, this was the standard opening phrase of all ancient creeds. The Nicene Creed also starts as follows:

“We believe in one God, the Father Almighty,

Maker of all things visible and invisible.”

But then it continues to perhaps contradict this opening phrase by adding that the Son is “true god from true god“.

The unbegotten

Ulfilas identified the Father as “the unbegotten.” Arius also mentioned “the unbegotten,” which is that which exists without a cause. That means that the Father is the ultimate Cause of all else.

Invisible

Ulfilas added that the Father is invisible. This is also stated a number of times in the New Testament (e.g. Col 1:15). Certainly, in the past, God appeared to people (theophanies), but an appearance is vastly different from God Himself. An appearance does not contain God in His fullness. It is not possible for God in His fullness to be seen, for He exists outside this visible realm.

Only-begotten Son

Ulfilas also believed in:

“His only-begotten Son,

our lord/master and God,

the designer and maker of all creation,

having none other like him.”

Our God

In this translation of Ulfilas’ statement, the Son is “our … God,” but this is faulty translation. It should be rendered “our god,” with a small “g.” As explained above, the Greek of the New Testament does not have a name for the God of the Bible. It uses theos; the common word for the pagan gods but added words such as “the” or “only” or “true” to identify “the only true god” (John 17:3). To say that the Son is “god” simply means that He is a immortal being, like the pagan gods. Consequently, Ulfilas followed up His description of the Son with the following explanation:

Therefore, there is one God of all,

who is also God of our God;

In this phrase, “our God” again refers to Jesus. This is similar to Hebrews 1:8-9, which also refers to Jesus as theos, but then says that the Father is His theos.

The phrases “only-begotten” and “none other like him” identify the Son as utterly unique.

Maker of all creation

Ulfilas described Son as the “designer and maker of all creation.” If He made all things, presumably, He was not made Himself.

Arius wrote that the Son was “begotten, or created, or purposed, or established.” In other words, Arius did not make a clear distinction between begotten and created. But after Nicaea, Arianism emphasized that the phrase “only begotten” means that the Son was not created. See, for example, the Long Lines Creed.

Only-Begotten

Ulfilas described the Son as the “only-begotten Son” of the “only one God the Father, the unbegotten.” The word “begotten,” which means that the Father gave birth to the Son, implies that the Son came from the being or substance of the Father. “Only-begotten” means that He is the only being that ever was born of God.

Because He was “begotten” of the being or substance of God, the Nicene Creed described the Son as homoousios with the Father. This word comes from homós (same) and ousía (being or essence) and means “same substance.” In Latin, it is consubstantial. In other words, the Nicene claimed that the Son is of the “same substance” as the Father.

In Arianism, this means that the Father and the Son have the “same substance,” just like we as people have the “same substance,” but remain different persons with different skills and capacities.

Trinitarian theology replaces the word “same” with “one” and understands homoousian as that the Father and Son have “one substance;” like three Persons with one body.

In his description of the Father and the Son, Ulfilas does not mention substance at all, which is a good thing, for that concept is not revealed in the Bible (Deut 29:29). It was an unfortunate addition to the Nicene Creed, probably due to the insistence of the emperor, who presided over the proceedings. (Listen to Kegan Chandler on the term “homoousios.”)

Subordinate

In Trinitarian theology, the Son is in all respects equal with the Father. In contrast, in Arianism, “begotten” means that the Son’s existence was caused by the Father, and that He is dependent on the Father, who alone is the uncaused Cause of all things. Arianism claims that the Bible reveals Him as subordinate to the Father; both before and after His existence as a human being. See the article – Subordinate.

The Father is God of our God.

What really sets Him apart from the pagan gods is not the title “god,” but that He is “the designer and maker of all creation.”

God, the Father – All instances of the word “God” in the quote from Ulfilas should be translated “god;” even when referring to the Father. Ulfilas made a distinction between the Father and the Son and the pagan gods in HOW he described Him, namely as the “only one god” who is “god of all” and also “god of our god.”

God of our God – As Ulfilas wrote, “there is one God of all, who is also GOD OF OUR GOD.” In other words, the Father is the Son’s god. The Bible similarly describes Jesus as “only-begotten god” (John 1:18) and “mighty god” (Isaiah 9:6); the Lord of the universe (1 Cor. 8:6), but the Father as Jesus’ “God” (e.g. Rev. 3:2, 12; Heb. 1:8-9; John 20:17). Paul described the Father is the Head of Christ.

Subordinate – Ulfilas closed by saying, “I believe the Son to be subject and obedient in all things to God the Father.”

The Holy Spirit is not a person.

Subject and obedient – Ulfilas furthermore believed “in one Holy Spirit, the illuminating and sanctifying power … Neither God nor lord/master, but the faithful minister of Christ; not equal, but subject and obedient in all things to the Son.” That the Holy Spirit is “neither God nor lord” implies that Ulfilas did not think of the Holy Spirit as a Person, but as a power, and a power that is subject and obedient in all things to the Son.

Subject and obedient – Ulfilas furthermore believed “in one Holy Spirit, the illuminating and sanctifying power … Neither God nor lord/master, but the faithful minister of Christ; not equal, but subject and obedient in all things to the Son.” That the Holy Spirit is “neither God nor lord” implies that Ulfilas did not think of the Holy Spirit as a Person, but as a power, and a power that is subject and obedient in all things to the Son.

Therefore, the Son is SUBORDINATE to the Father and the Holy Spirit is SUBORDINATE to the Son.

No Trinity in the first four centuries

Ulfilas did not believe is the Trinity. For him:

The Father alone was God.

The Holy Spirit is not a Person.

There is no mention of three Persons in one Being.

It is often said that Arians do not believe in the traditional doctrine of the Trinity, which is true. However, the concept of the Trinity, as we know it today, did not yet exist in Arius’ day.

First 300 years – In the first three centuries, the church fathers did not think of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit as three Persons in one Being. Tertullian did use the word “trinity,” but he used it to refer to a group of three distinct beings; not use in the sense of a single being.

Nicene Creed – Neither does the Nicene Creed contain the Trinity concept, as a careful reading of that creed will show. The purpose of that creed was to say that the Son is equal to the Father; not say that they are one Being; the same God. It does say that they are homoousios (of the same substance), but that does not mean that they are one being. We may argue that human beings are of the same substance, and that does not make us all one being.

The Trinity doctrine was formulated later in the fourth century, perhaps by the Cappadocian Fathers, probably in response to the Arian criticism that the Nicene Creed creates the impression of two gods and can be accused of polytheism.

Three Forms of Arianism

In fact, as debates raged during the five decades after Nicaea, in an attempt to come up with a new formula, different forms of Arianism evolved. Three camps are identified by scholars among the opponents of the Nicene Creed:

Different Substance

One group, similar to Arius, maintained that the Son is of a different substance than the Father. They described the Son as unlike (anhomoios) the Father.

Similar Substance

The Homoiousios Christians (only an “i” added to “homoousios”) accepted the equality and co-eternality of the persons of the Trinity, as per the Nicene Creed, but rejected the Nicene term homoousios. They preferred the term homoiousios (similar substance). This is very close to the different substance view of the Arians. Therefore, they were called “semi-Arians” by their opponents. (See homoousia.)

No speculation about Substance

Homoian Arianism maintained that the Bible does not reveal whether the Son is of the same substance as the Father, and we, therefore, should not speculate about such things. They avoided the word ousia (substance) altogether and described the Son as homoios = like the Father. Although they avoided invoking the name of Arius, in large part they followed Arius’ teachings. RPC Hanson (The Search for the Christian Doctrine of God. Edinburgh: T&T Clark. pp. 557–559) lists twelve creeds that reflect the Homoian faith in the years 357 to 383.

None of these groups, therefore, adopted the Trinitarian approach of “one substance.”

In the fourth century, these differences were taken quite seriously and divided the church; similar to the denominations in Christianity we know today. Depending on the interpretation supported by Emperor Constantius, for example, wavered in his support between the first and the second party, while harshly persecuting the third.

Historians, unfortunately, categorize all three positions as Arianism, but there are important differences between these views.