This is an article in the series on the historical development of the Trinity doctrine.

This is an article in the series on the historical development of the Trinity doctrine.

These first articles discuss the views of the church fathers in the first three centuries:

-

- Were they Trinitarians?

- Did they think of God as One Being but three Persons?

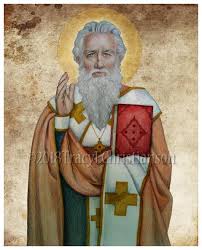

Previous articles discussed the views of Polycarp and Justin Martyr. The current article reflects the thoughts of Ignatius of Antioch (died 98/117). All three of them were killed for their faith.

Triadic Passages

A Triadic passage is one in which the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are mentioned together. A famous example is Matthew 28:29:

“Baptizing them in the name of

the Father

and the Son

and the Holy Spirit”

Ignatius also mentioned the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit together in a single sentence:

“In Christ Jesus our Lord,

by whom and with whom be glory and power

to the Father

with the Holy Spirit for ever” (n. 7; PG 5.988).

However, just mentioning them together does not mean that they are one Being or that they are equal. It only means that they are related. Take for example:

“One Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God” (Eph 4:5)

Here, Paul mentions the Son as “Lord” and the Father as “God.” But he does not mention the Holy Spirit. He adds “faith” and “baptism.” This does not mean that these four are equal or one and the same. It only means that they belong together.

The Father alone is God.

That that triadic passage does not mean that the Persons of the Trinity are equal can be seen when Ignatius identifies the Father alone as God:

Thou art in error when thou callest

the daemons of the nations gods.

For there is but one God,

who made heaven, and earth, and the sea,

and all that are in them;

and one Jesus Christ,

the only-begotten Son of God,

whose kingdom may I enjoy. (Martyrdom of Ignatius 2)

Here, Ignatius refers to “gods,” “God,” and Jesus Christ. And he adds the word “one” before “God” and before “Jesus Christ.” This is similar to 1 Corinthians 8:4-6, which reads:

“Even if there are so-called gods

whether in heaven or on earth …

yet for us there is but one God, the Father,

from whom are all things and we exist for Him;

and one Lord, Jesus Christ,

by whom are all things, and we exist through Him.”

Both these statements explicitly identify the “one God” as someone distinct from the one Lord Jesus Christ. In other words, the Father alone is the “one God.”

The Only True God

Ignatius further wrote:

But our Physician is

But our Physician is

the only true God,

the unbegotten

and unapproachable,

the Lord of all,

the Father and Begetter

of the only-begotten Son

We have also as a Physician

the Lord our God Jesus the Christ1Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson, eds., The ante-Nicene Fathers, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1975 rpt., Vol. 1, p. 52, Ephesians 7.

The following discusses specific phrases from this quote:

Unbegotten

Ignatius describes the Father as “unbegotten” in contrast to the Son who is “begotten.” The ancients created the term “unbegotten” to indicate that the Father alone exists without a cause. See, for example, the Long Lines Creed. The Son received His existence from the Father.

Unapproachable

Ignatius also describes the Father as “unapproachable.” 1 Timothy 6:16 similarly says that the Father “alone possesses immortality and dwells in unapproachable light.” His unapproachability is related to His invisibility. The Bible often states that God is invisible. For example:

“His beloved Son … is the image of the invisible God” (Col 1:14-15).

Since the Son is both visible and approachable, He is not that “invisible” and “unapproachable” God.

Our God, Jesus the Christ

Ignatius describes the Son as “our God.” Trinitarians use such phrases to argue that the church fathers did believe that Jesus is God. Since many writers in the first 300 years referred to Jesus as “our god,” this is discussed in the article, Jesus, our god.

In summary, the ancient Greek language did not have a word exactly equivalent to the modern English word “God:”

In modern English, we use the word “God” as the proper name for the Ultimate Reality; for the One who exists without cause.

The ancients Greeks did not have such a word. They only had the word “god” (theos). This word was used for the Greek Pantheon, the gods of the nations, as well as for the One who exists without cause. Therefore, whether to translate theos as “God” or “god” depends on the context.

According to the translation above, Ignatius (and other church fathers) described Jesus as “our God” and the Father as “the only true God:”

The phrase “only true God” comes from John 17:3, where it describes the Father. This phrase is somewhat illogical because only one God (one Ultimate Reality) exists. The phrase is saying, similar to 1 Corinthians 8:6, that many gods exist but only one of them is truly “god.” So, to reflect the true meaning of the Greek, it might have been appropriate to translate it as “only true god.”

Similarly, the Greek says that the Son is “our god.” To translate theos, when it describes the Son, as “God,” is an application of the Trinity doctrine. It must not be taken as proof of that doctrine.

Basically, the Greek word “theos” means an immortal being with supernatural powers. That description certainly fits the One we know as Jesus Christ. For that reason, and since these church fathers maintained a strict distinction between the Almighty and Jesus Christ, they referred to Jesus as “our theos” as opposed to the “one true theos.” In that instance, “our theos” is better translated as “our god.”

For a further discussion, see – When referring to Jesus, how should theos be translated?

Incarnation

Ignatius continues to describe the Son:

The only-begotten Son and Word,

before time began,

but who afterward became also man, of Mary the virgin.

For ‘the Word was made flesh.’

Being incorporeal, He was in the body;

Being impassible, He was in a passible body;

Being immortal, He was in a mortal body;

Being life, He became subject to corruption,

that He might free our souls from death and corruption,

and heal them, and might restore them to health,

when they were diseased with ungodliness and wicked lusts.2Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson, eds., The ante-Nicene Fathers, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1975 rpt., Vol. 1, p. 52, Ephesians 7.

Specific phrases from this quote are discussed below:

Before time began

Ignatius says that the Son was begotten “before time began.” That means that the Son has ‘always’ existed; that He existed as long as time existed.

The ancients assumed, based mostly on Plato’s philosophy, that time began when all things were created. Outside time, there exists a timeless infinity, for God exists outside time. The Father begat the Son in that incomprehensible infinity beyond time. If we use the word “before” metaphysically (not in a literal time sense), then we can say that the Father existed “before” the Son. However, from the perspective of creation, the Father and Son are co-existent.

Afterward became also man

Not all Christians believe that Jesus existed before He became a human being. See, for instance, Dr. Tuggy’s Case Against Preexistence. But, with exceptions, the ancients did believe in Christ’s pre-existence.

Incorporeal

According to Ignatius, before the Son became a human being, He was incorporeal (intangible). This seems like speculation. Where does the Bible say this? He is the perfect image of the invisible God (Col 1:15). Does that not mean that He is visible?

Impassible

Ignatius also said that the Son, before He became a human being, was impassible (incapable of suffering or feeling pain). “Impassibility” is a concept from Greek philosophy and also seems to be speculation when applied to the God of the Bible or to the pre-existent Jesus Christ.

In Greek philosophy, only the High God is impassible. To say that the Son is also impassible puts a very high view on Him.

Ignatius is here consistent with the Nicene Creed of 325. That Creed condemns “those who say (that the Son) is alterable or changeable.” This shows the influence of philosophy on that Creed.

Immortal

The statement that the Son was immortal seems to contradict the Biblical statement that the Father “alone possesses immortality” (1 Tim 6:16). However, there are two kinds of immortality:

Only the Father exists without cause and is therefore essentially (unconditionally) immortal.

The Son received His immortality from the One who exists without cause. Even created beings will become immortal “when this perishable will have put on the imperishable, and this mortal will have put on immortality” (1 Cor 15:54). But this remains conditional immortality. We will be immortal, not because we cannot die, but because God will not allow us to die.

Human souls, therefore, are not essentially immortal. Souls can die. “Fear Him who is able to destroy both soul and body in hell” (Matt 10:28). The immortality of human beings will always be conditional.

Being Life

The description of the Son as “being life” is perhaps explained by John 5:26:

“Just as the Father has life in Himself,

even so He gave to the Son also to have life in Himself.”

On the one hand, it means that, just like He received His existence from the Father, He also received “life in Himself” from the Father. Since the Father is the only Being who exists without cause, all other beings, including His only-begotten Son, are subordinate to Him.

On the other hand, there are only two Beings who have “life in Himself.” This testifies to a uniquely close relationship and makes the Son very similar to God. Again, He is the perfect (but visible?) image of the invisible God (Col 1:15).

Physician

Ignatius described both the Father and the Son as physicians. He also describes the sinner as “diseased” and God’s aim as to “heal … restore … to health.” “Physician” is a most appropriate description of God’s attitude towards sinners: He is not an independent Judge, but a passionate Father (or Mother, for those of us who did not experience a loving father).

CONCLUSIONS

For Ignatius, the Father is “the only true God” and the only Being who exists without a cause. He distinguished between the “one God” and the “one Jesus Christ.”

According to the English translation, he described Jesus Christ as “our God.” However, the phrase “our God” is an interpretation. The Greek text simply says “our god.” To translate it as “our God” is an application of the Trinity doctrine; not proof thereof.

On the other hand, Ignatius did say that the Son was begotten “before time began.” That means that the Son has ‘always’ existed; that He existed as long as time existed.

There is also no evidence in the quotes above that Ignatius thought of the Holy Spirit as a self-aware Person, or that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are of one substance or one Being, as per the Trinity doctrine.

Other Articles

FOOTNOTES

- 1Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson, eds., The ante-Nicene Fathers, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1975 rpt., Vol. 1, p. 52, Ephesians 7.

- 2Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson, eds., The ante-Nicene Fathers, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1975 rpt., Vol. 1, p. 52, Ephesians 7.

Over the centuries, Arius was always accused of mixing philosophy with theology. This article shows that that is not true. There are two ways in which Greek philosophy could have influenced the debate in the fourth century:

Over the centuries, Arius was always accused of mixing philosophy with theology. This article shows that that is not true. There are two ways in which Greek philosophy could have influenced the debate in the fourth century: “‘Classical theism’ is the name given to the model of God we find in Platonic, neo-Platonic, and Aristotelian philosophy.” (

“‘Classical theism’ is the name given to the model of God we find in Platonic, neo-Platonic, and Aristotelian philosophy.” (